Cary McStay is missing. Not in real life. But in tweets by men on a platform where many widely read Twitter conversations focus on research, history, records, archives, and special collections. And the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) where Cary works. Of the 10 tweets about Cary by name as I write this post, 2 are by Dr. Miriam Posner and 8 are by me. That’s it. All tweets describing or acknowledging or thanking her for her work come from women. One is a UCLA iSchool professor and the other a Federal historian and archivist who knows Cary in person.

No one else.

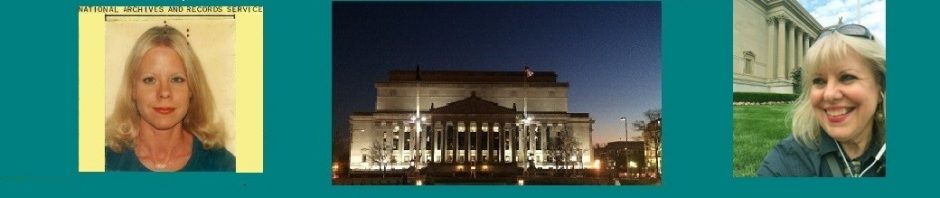

Why did I check Twitter? I just tagged Cary in the National Archives Catalog in a photo series showing her at work in 2008 with male and female colleagues. Cary joined NARA in 2006 as an archives specialist after working briefly for the Library of Congress. She holds a B.A. in History and a Master’s in Library and Information Science with a specialization in archives and records management. Cary has been NARA’s Nixon White House tapes supervisory archivist since 2010.

Although Cary keeps a personally low profile, some NARA press releases and a few news articles refer to her work. I can’t say why no men I Follow or once Followed on Twitter who know who she is never have tweeted her name. But if you’re an educator, you may have a future Cary in your classroom right now studying for a History B.A. Or a graduate degree in one of several knowledge producing or using academic fields.

One of your students may write op eds some day that support knowledge workers. A humanizing approach to advocacy resonates broadly with practitioners, enables consideration of suggestions, and showcases the type of skills a writer such as T. J. Stiles uses in biography. (Speaking for myself, humanization also gives readers breaks from seeing or hearing demagoguery.) As our professional associations show in their breadth of outreach, humanizing history and archives practitioners enriches understanding of both sides of the physical or virtual research desk.

NARA has greatly opened up since Kate Theimer, a widely read and respected blogger, described its culture as relatively closed in 2008-2009. Its online public access Catalog enables not just NARA employees and volunteers but any users of records outside the agency to create accounts and tag and add comments about content. Since June 2021 NARA’s Catalog includes on each page an autogenerated banner with a potentially harmful content alert (here’s what that means). The Catalog alert reflects the work of the National Archives’ own employees. They developed it within the framework of the NARA Task Force on Racism that Archivist David Ferriero established in June 2020.

NARA’s workforce composition is about 50-50 men and women. Just as some archivists, historians, and librarians write Wikipedia entries about women to provide knowledge about their contributions, I’m tagging women I know or recognize in the NARA Catalog. Two photos I tagged this weekend show Cary assisting researchers at Archives 2, NARA’s newest facility in the Washington suburbs. It gave me great joy to tag images of Cary among a group of colleagues early in her career. Some still work at NARA, others moved on to academic positions or jobs in different Galleries, Libraries, Archives, Museums (GLAMs).

The Nixon Presidential Materials Staff moved into Archives 2 shortly before my twin sister, a NARA supervisory archivist, oversaw the move of civil national security classified records to A2 in 1994. That the Nixon tapes unit remains in College Park may explain in part why some former employees discuss front room issues (reference desk, museums/public programs) and access to long open documents more so than back room special media processing. After NARA established a Federal Nixon Presidential Library and Museum in California in 2007, it transferred all Nixon records functions except tapes processing from College Park to Yorba Linda.

In most presidential records units, NARA employees working as providers (arranging, describing, and doing disclosure review of holdings) or users of records (NARA oral history initiatives, content creators for exhibits or public programs) share space in the same building. No workplace is stagnant. But as you go about your own important duties (complexity and challenges may vary over time), there’s nothing like seeing backroom colleagues in person to keep their contributions in mind. As the rest of the Nixon records staff relocated to California, Cary and the tapes staff stayed in touch with presidential library peers virtually. In 2020, SAA members came to know Cary when she and NARA colleague Daniel Rodriguez presented a virtual session on “The Nixon Tapes in the Digital Age.”

A research room perspective (both sides of the reference desk) showed on Twitter in February 2019, when the New York Times published an article with a potentially confusing headline, “The Obama Presidential Library That Isn’t.” (Archives and library beat reporters often write as users of records which resonates with many researchers). I’m glad to say most stakeholders searched for and welcomed information and clarification from NARA. As much as I support NARA and enjoy sharing kudos, some of its officials may not have anticipated some of the questions that arose in 2019. As a learning organization, it recognized this and adjusted.

That 95% of Obama’s records are electronic only (no paper copy) wasn’t widely known to most NYT readers. Return on investment and consideration of endowment funding also meant Obama’s decision to forgo a traditional presidential library didn’t surprise me. Among people I Followed on Twitter in 2019, I saw a strong museum and records user rather than a records provider perspective in reactions to Jennifer Schuessler’s NYT article. Tweets such as “dumb” and “ill-advised” and “illiberal” about Obama’s decision from a handful of scholars and archives practitioners pointed to outreach challenges and opportunities. Writing in The Atlantic, Professor Dan Cohen embraced an opportunity to update biographer Robert Caro’s well known admonition to turn “turn every page” means for the digital age.

NARA emphasizes information gathering and sharing with individuals and groups (the American Historical Association (AHA), the Organization of American Historians (OAH), the Society for Historians of American Foreign Relations (SHAFR) and archives and records associations). I’m grateful SHAFR, which took no position on the matter and welcomed different perspectives, published my journal essay about the Obama records in the September 2019 issue of Passport. I later posted at my blog an illustrated version, slightly revised for greater emphasis on how we all now are electronic content creators facing records management, retrieval and access issues at home and at work.

Records access workers at NARA usually have users (internal and external) in mind. Having done such work as a National Archives employee, I know that for many archivists awareness of the public trust and the impact on users of releasing or restricting information is part of routine daily work. In some NARA presidential libraries, people specialize throughout their careers in archival disclosure processing or in education and museum and public programs work. In others they switch around.

Random chats in the buildings we work in or visit suggest who we are beyond formal workplace presentations (photo). When I ran into her in the hallway outside her office in 2018, Cary told me how one of her team members, a man I knew as a friend and colleague, was about to receive Archivist’s Awards Ceremony recognition for which she had nominated his work.

Jeanne Schauble, who began her career in NARA’s Office of Presidential Libraries, the same unit in which I once worked, exemplified a low key public service ethos worth considering when navigating complex issues online. The NARA Catalog places her in a well deserved spotlight in August 2010, when she received the Archivist’s Lifetime Achievement Award for her records disclosure declassification work. Jeanne was my late sister’s boss and a friend to us both.

Steve Aftergood noted at his Secrecy News blog in 2011 that “Jeanne Schauble, the longtime director of declassification at the National Archives, died last October. She helped oversee and implement the declassification of more than a billion pages of historical records since 1995….As far as we could tell, no obituaries for Ms. Schauble or Mr. Resnick appeared in any national newspaper. They weren’t famous. But they were honest, honorable and skilled public servants. Anyone who crossed their paths will remember them.”

In 2014, historians Luke Nichter and Douglas Brinkley spoke at NARA about their book, The Nixon Tapes, 1971-1972. Archivist David Ferriero noted in his welcoming remarks that,

“It is particularly fitting that Brinkley and Nichter grace our stage today for as they cite in their acknowledgements ‘This book…benefited greatly from the help of many helpful archivists…first at what was known at the Nixon Presidential Materials Project, then the Nixon Presidential Library.’

Singled out are many of the people in the room today so thank you on behalf of the authors.

And thank you also from the Archivist of the United States for the work that you have done to make these tapes available.”

As David spoke, Cary sat with three archivists who once had worked on the Nixon tapes, among them Rod Ross, a PhD historian (seated at right). Dr. Nichter thanked Cary and other archivists by name from the stage. Luke’s book acknowledgements always are thoughtful and attentive to those who assist him, including in processing records for release.

I handed my iPhone 4 to a NARA employee to take the reunion photo below. A professional NARA staff photographer, Jeff Reed, photographed Luke at the book signing that followed. Does this symbolize what people often see online–some work in well-deserved sharp focus, other work less so? History, political science, and library and information science educators can bring more backroom work into sharper focus as Luke Nichter has done and Rod Ross showed in an unexpected way.

Rod did an insightful, useful series of oral history interviews for the National Archives in the 1980s. He also was a subject of a NARA oral history interview in 2015 by History Office intern Rebecca Brenner (as of August 2021 Rebecca Brenner Graham, PhD–congratulations!). Rod described how he started as an archives-technician, the same position in which I and many others at the National Archives started, including Chief Operating Officer William (Jay) Bosanko. He first worked with the Nixon tapes in the National Archives’ Office of Presidential Libraries. After promotion to archivist he did exit interviews and other assignments at a now closed White House liaison office.

Recruited to apply for a supervisory position in NARA’s Printed Archives Branch, Rod admitted the move didn’t work out: “It turned out that I really wasn’t a good fit to be a supervisor.” He instead became a leading NARA expert on legislative records. As I noted in my last blog post, Ferriero once stepped out of a board meeting for 15 minutes so he could introduce an author lecture for a book which acknowledged Rod’s contributions in the research process. Rod, who retired in 2016, was present to hear David’s remarks.

Some job cultures welcome publicly expressed self-awareness and open admission of willingness to try and fail but others do not. As an educator, you don’t know where your students will thrive. Some need something close to what you chose and need, others something very different.

If you wish, you can prepare them for seeing and recognizing what others have done. And thinking about their options in a very tight academic as well as GLAM job market. Centering one choice in in the classroom doesn’t necessarily bring clarity and can limit considering options or exploring cause and effect. (I have some experience with trial and error here.) It’s worth looking at online through lines to see who’s there and why. And who may be missing.

Some of your students may one day work as managers or as supervisors, as Cary does now. Or as Federal historians, as I did after leaving NARA. Or as administrators with people in their care. They’ll need to see varied human elements that make up the big picture even as individuals in group photos focus on their own interests and needs. This takes similar skills to figuring out a history narrative or crafting a biography that illuminates who someone was and why they acted as they did. So in exploring job choices in class, consider including Cary McStay, Jeanne Schauble, Rod Ross, and others in the back as well as the front room, up and down the ranks.

Thank you for this wonderful and thoughtful article about Cary, our daughter. We are very proud of her and her accomplishments. I know, and you know, the service, professionalism, and excellence she brings to her work day. Hats off to the other hard-working archivists mentioned in the article. Cary keeps the public trust, provides access, and educates all who use archives for historical research, museum work, and public use. Kay McStay

LikeLiked by 1 person

A wonderful tribute, Marja, and nice to see it reached Cary’s parents!

LikeLiked by 1 person