A movie about policy disputes includes a scene where a supplicant visits a government official in his home as he sits at a table with his family. And asks for a job. The official refuses and the man leaves in anger. The official’s family demands he take action against the threat the job seeker represents to his livelihood. But the official stands firm on the rule of law. He asks his son-in-law how he could stand upright if he cut down laws one by one to harm someone, then lost protection himself as strong winds blew. The official tells his family he gives everyone benefit of law.

An article this morning about the Presidential Records Act (PRA) fails to center a statute which mandates the transfer–not giving, selecting, choosing, or using in a museum–of records of a president and statutorily covered White House aides into the legal custody of the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). The reporter includes no quotes from current or former National Archives employees who have worked on PRA transitions.

One such employee, Mark Fischer, wrote a promotion program essay in 1990 for NARA (available internally and to the public) about the move of Ronald Reagan’s PRA records to California. President Reagan’s records were the first transferred to NARA under the PRA. Fischer worked on the transfer as a temporary detailee to the White House in 1989 while employed as a line archivist on NARA’s Nixon Presidential Materials Staff. He transferred from the NARA Nixon Presidential Library and Museum to the Ford Presidential Library in 2009 and retired in 2018. His essay (“A study of the planning and archival control methods for the movement of the Ronald Reagan presidential records”) is available in the NARA library in its College Park, MD facility. And also in administrative records of the Nixon Presidential Library’s predecessor unit.

NARA’s FOIA electronic reading room includes detailed information on how presidential transitions work in the context of recent changes of administrations. National Archives officials also did outreach interviews on presidential transitions for AHA, OAH, and UMD iSchool grad students in 2021. Although underutilized by scholars, journalists, and pundits, these make clear that as he leaves office, the president does not select records to place under the control of NARA. But rather that all materials covered by the PRA as related to official functions automatically transfer to NARA’s legal custody the day a president leaves office. And that by law NARA takes charge of PRA covered paper and electronic records (99% of Trump’s are electronic, 95% of Obama’s electronic) at 12 noon January 20 as a president’s one or two term tenure ends.

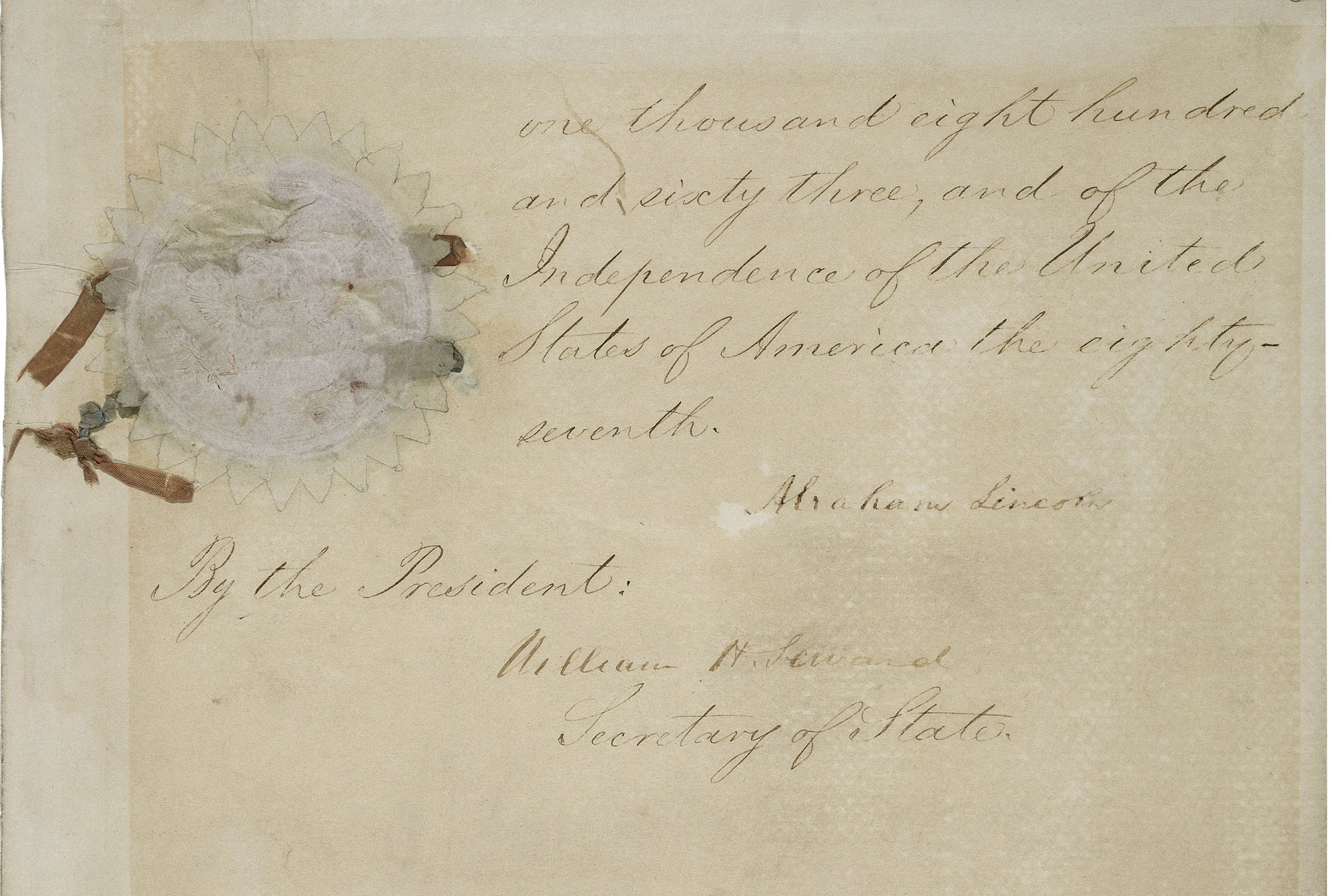

Today’s article fails to fully explore the origins of the PRA. “‘Nixon showed he wasn’t interested in following precedent,’ [Bob] Clark said. ‘And we’re in one of those crossroads moments now.’” Yet Congress passed the Presidential Recordings and Materials Preservation Act (PRMPA) in 1974 to cover his records because Nixon expected to follow the precedents established by his predecessors. Presidents Roosevelt through Johnson and their designees selected what to donate as personal property, with deed of gift restrictions, to the government–the National Archives.

While none of Nixon’s predecessors were under investigation as they left office, or stipulated publicly destruction of records as significant as Nixon’s tapes, there’s no way to determine what records they did not include in such donations and what percentage, of whatever significance and however small in volume, they destroyed rather than donating to the National Archives. They could do so as by custom White House records then were treated as a president’s personal property. A provision in PRMPA created the public documents commission which recommended passage of the PRA and established future government ownership of covered White House records.

None of the quotes the reporter used (Clark; Paul Musgrave (“it is, in fact, very difficult to get critical materials into the [presidential library’s] museum”); Tim Naftali (“President Trump’s decision to withhold or take material with him”) make clear how departure records management works in the PRA process. White House counsel and designated officials working for the president traditionally oversee records transfer during transitions. Greater clarity in quotes to reporters as to which functions of a presidential library or museum fall under the PRA helps improve civic literacy. NBC’s description of Obama’s presidential records and construction of his presidential center, which is separate from NARA’s Obama presidential records unit, may have confused some readers.

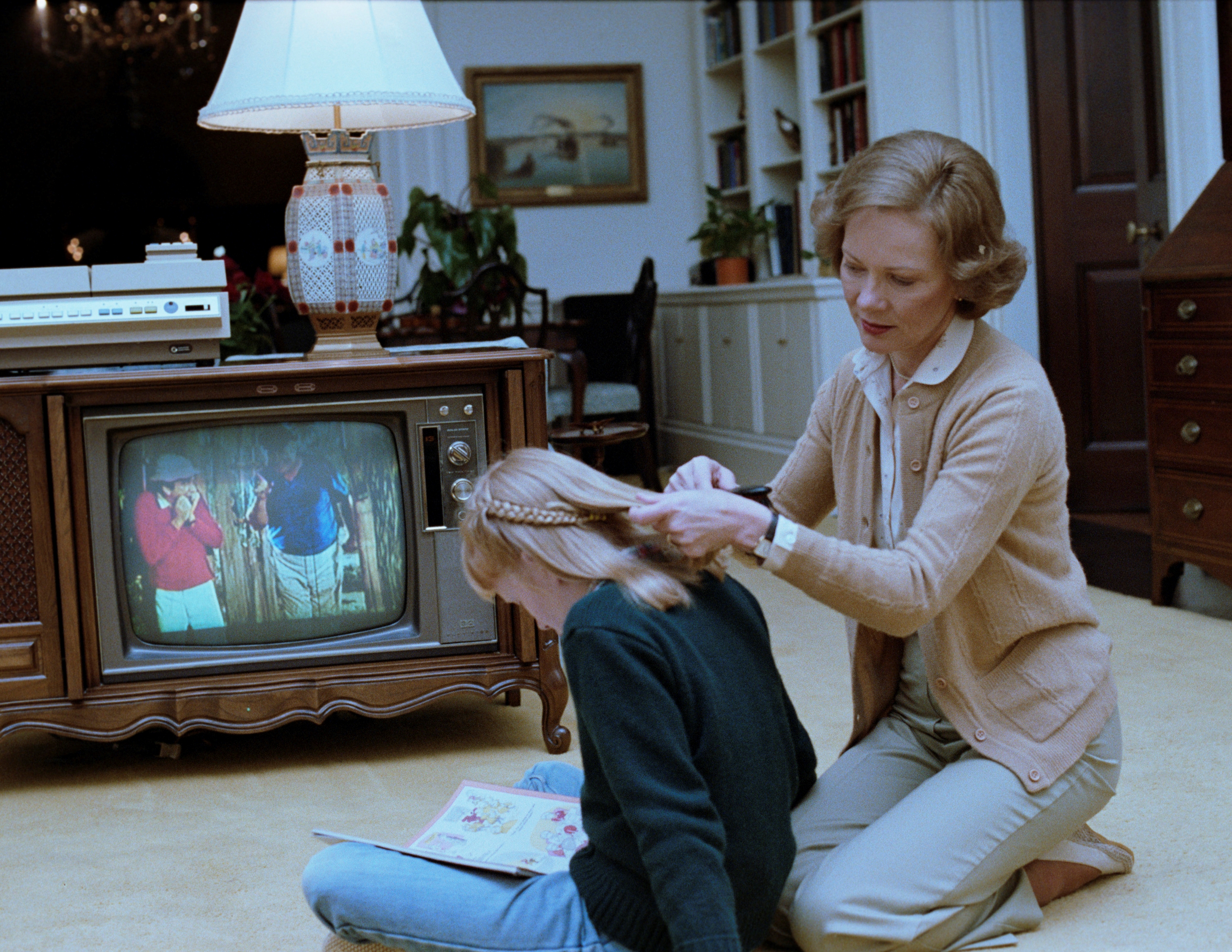

Barack Obama decided in May 2017 that given his records are 95% electronic (no paper version), he would not raise money to build a traditional monumental presidential library and museum with a set endowment to cover a small part of operating costs when taken over by NARA under a joint operating agreement. (The approach used by Presidents Ronald Reagan through George W. Bush.) But that his records, already in NARA’s legal and physical custody as of January 20, 2017, would stay in space the government leases or maintains using appropriated funds rather than in a huge library constructed through private fundraising. Former President Obama instead is building a privately funded Presidential Center which will contain no original presidential records as those are and will remain in NARA’s custody under the control of its Barack Obama Presidential Library operating unit.

It’s time to center legal transfer to NARA custodial units of statutorily controlled presidential records and stop talking about NARA “getting” records from presidents for presidential libraries (or museums). Or PRA covered presidents “selecting” as they leave office items for the NARA presidential records operating units mandated by law. As Obama’s law-premised choice reminds us, the establishment of existing presidential library-associated museums, however valuable, has been discretionary, not codified in law as inherently governmental.

Centering presidents rather than statutes in framing presidential records issues may play a part in the current myth, shared by some members of the public on Social Media, that Obama “took” his classified and unclassified records to Chicago as he left office and failed to turn any over to NARA. The National Archives issued a statement last month reminding the public that

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) assumed exclusive legal and physical custody of Obama Presidential records when President Barack Obama left office in 2017, in accordance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA). NARA moved approximately 30 million pages of unclassified records to a NARA facility in the Chicago area where they are maintained exclusively by NARA. Additionally, NARA maintains the classified Obama Presidential records in a NARA facility in the Washington, DC, area. As required by the PRA, former President Obama has no control over where and how NARA stores the Presidential records of his Administration.

August 12, 2022, statement

Such myths may have played a part in threats by some members of the public against the NARA Obama Presidential Library unit’s government-leased suburban Chicago facility. And threats against others employed by the National Archives. Language matters, framing matters, word choices for sound bites a reporter chooses to use matter because that’s all the public will see regardless of whatever else someone says when interviewed. Especially when civil servants face the threats and vitriol described in a recent NARA Notice made public by the agency. The National Archives officially posted the Notice for all to read on its website.

This wasn’t a selective leak, surreptitiously made available by current staff to past employees or others outside government without access to other nonpublic information. A practice I oppose and condemn as corrosive and antithetical to the authorized archival disclosure most NARA archivists honor. Rare within NARA, unauthorized disclosures go back to a 1993 document leak to Nixon’s lawyers by internal critics of Acting Archivist Trudy Peterson’s policies. A leak which surprised and drew a well-deserved rebuke from the bench from District Court Judge Royce C. Lamberth in 1993 when he presided over a hearing on litigation over access to the Nixon tapes.

On August 24, 2022, Acting Archivist Debra Steidel Wall provided an update to all employees on Trump presidential records. In an integrity-based release, NARA shared it with all members of the public, as well. The Acting Archivist provided context:

In February, former Archivist of the United States David S. Ferriero shared with you information about Trump Administration Presidential records and the National Archives. In NARA Notice 2022-082 and NARA Notice 2022-087, he wrote that NARA received 15 boxes that contained Presidential records from former President Trump’s Mar-a-Lago property in Florida, including items marked as classified national security information, and, accordingly, had been in communication with the Department of Justice. He also shared that NARA staff did not visit or “raid” the Mar-a-Lago property; that representatives of President Trump informed us that they were continuing to search for additional Presidential records that belong to the National Archives; and that some of the records we received at the end of the Trump Administration included paper records that had been torn up.

We continue to be unable to comment on potential or ongoing investigations.

However, this week a representative of President Trump released the text of a letter I sent to Trump representative Evan Corcoran on May 10, 2022. Typically, we do not publicly share non-routine correspondence with former Presidents and their representatives but, under these circumstances, we have released an official copy of the letter ourselves. The letter is now available on our FOIA Electronic Reading Room, at https://www.archives.gov/foia/pra-trump-admin.

After summarizing the letter to the former president’s lawyer, Debra Steidel Wall provided public links to NARA correspondence with the Congress. She stated, “In those letters, I report that, since our initial referral, the DOJ has been exclusively responsible for all aspects of its investigation, and NARA has not been involved in any searches that it has conducted.” She also linked to NARA’s August 12 statement on the Obama records which I quoted above.

The Acting Archivist of the United States noted,

The National Archives has been the focus of intense scrutiny for months, this week especially, with many people ascribing political motivation to our actions. NARA has received messages from the public accusing us of corruption and conspiring against the former President, or congratulating NARA for “bringing him down.” Neither is accurate or welcome. For the past 30-plus years as a NARA career civil servant, I have been proud to work for a uniquely and fiercely non-political government agency, known for its integrity and its position as an “honest broker.” This notion is in our establishing laws and in our very culture. I hold it dear, and I know you do, too.

She concluded by thanking NARA employees for their dedication to the mission of a “fiercely nonpolitical agency,” one in which they uphold the public trust with “professionalism and integrity.” She closed her remarks to the employees of the National Archives with an affirmation: “We will continue to do our work, without favor or fear, in the service of our democracy.”

In talking to each other, formulating answers for reporters, writing op eds which include perspectives shaped by personal experiences (policy support or opposition; jobs applied for, attained or not; pride in separate accomplishments in disparate NARA functional areas or settings), let’s strive to center the law, not individuals. And do this whether we worked in a PRA environment or not.

I mostly worked PRMPA as a NARA archivist team leader in its Office of Presidential Libraries. But also did some PRA work as a NARA temporary detailee to the Reagan White House Office of Records Management (WHORM). You can see in a government publication how WHORM handled its work during the Reagan, Bush 1, Clinton, Bush 2 administrations in a transition essay by its former director,Terry Good.

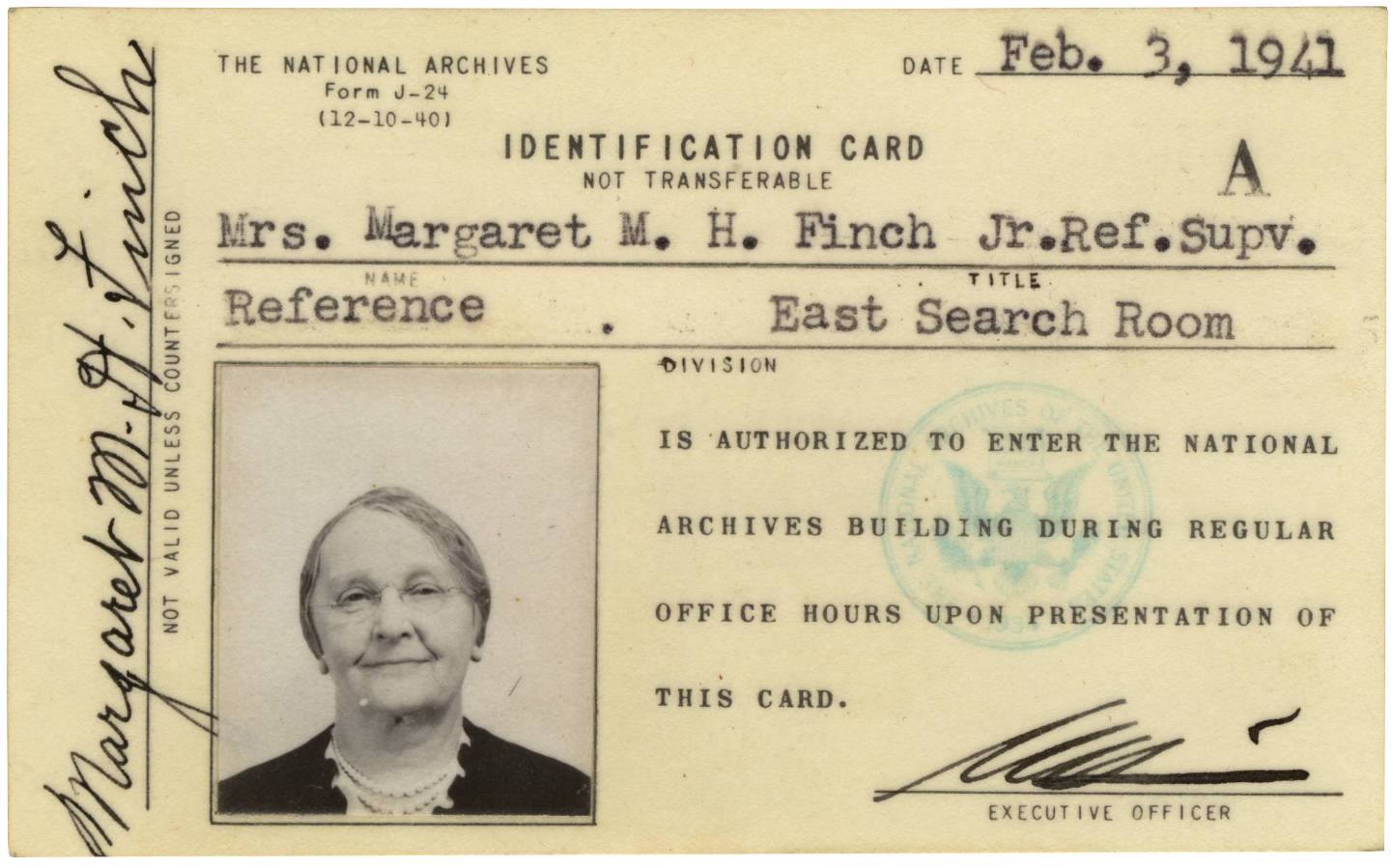

Centering laws is what our present and former National Archives PRA-aware colleagues have done from November 2009 to the present as archives technicians; archives specialists; archivists; audio-visual experts; mission-support staff; NARA’s White House liaison officials; lawyers; public affairs experts; Congressional relations advisors; program and staff office managers and executives; the senior management team; and the top NARA administrator.

Let’s honor these public servants of all ranks by doing the same.